Radiohead closes the circle

Twenty years and about two months ago, I was sitting on a plane en route to Spain from New York, playing an advance copy of Radiohead’s OK Computer over and over again. This was part of my preparation for interviewing all five members of the band during the album’s global media launch event in Barcelona. (When was the last time that a piece of popular music was deemed important enough, and potentially lucrative enough, to warrant a global media launch event? Those were the days.)

All the repeat listens yielded rewards aplenty; OK Computer was an absorbing, compelling modern masterpiece. But a couple of things bothered me. I didn’t get why the band had chosen to include “Lucky”—a great track, but a track they’d already put on a benefit album nearly two years before—in the final running order. And I was baffled that several excellent, not-previously-released songs I’d heard them play live within the past two years were nowhere to be found.

It’s funny to remember these personal quibbles now, given the lofty seat that OK Computer has since assumed, deservedly, in the rock pantheon. The passage of time has turned the album into the audio equivalent of a stone tablet, making it tough for anyone to imagine how it could ever have sounded any different from the artifact we know. Still, a large number of Radiohead followers, including me, have never forgotten those missing songs. And I’m thrilled to learn that the members of Radiohead haven’t forgotten them either.

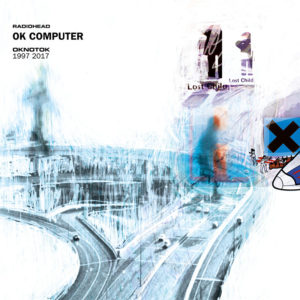

The evidence for this? OK Computer’s 20th-anniversary reissue, subtitled OKNOTOK 1997 2017, includes three of them: “I Promise,” “Man of War,” and “Lift,” all in immaculate studio versions, just what fans have been coveting for two decades. Because the band hasn’t provided any session documentation for these recordings, it’s hard to know when they were completed, but based on the youthful tone of Thom Yorke’s voice, I’d wager they’re real 1996-97 vintage.

Of the “new” tracks, “I Promise” is the simplest and most immediately engaging. On this brooding ballad, Yorke’s operatic falsetto channels the Roy Orbison of “It’s Over,” conveying a sense of devotion that has long outlasted any useful, or healthy, purpose (“Even when the ship is wrecked/I promise/Tie me to the rotting deck/I promise”). “Man of War” is a welcome reminder of the knack Radiohead once had for mining a particularly—pardon the expression—rockist sense of drama, rooted in the ’70s AOR of Queen and Pink Floyd.

And then there’s “Lift,” the tune whose non-inclusion on OK Computer perplexed me the most back in 1997. How could they have ditched a song with such a soaring chorus, whose final lines (“Empty all your pockets/‘Cause it’s time to come home”) I could easily envision stadiums full of people bellowing?

Hearing the studio version of “Lift” at last, with the benefit of hindsight, the band’s decision is easier to understand. The song revolves around the same kind of death/rebirth-through-calamity metaphors as “Airbag,” OK Computer’s opening track. In the latter song, a car crash is the calamity. In “Lift,” the situation’s more fanciful; our protagonist, helpfully named Thom, has been trapped for some time in an elevator (the titular lift), but not just any old elevator—this one’s “in the belly of a whale at the bottom of the ocean.” A bit Biblical, a bit Melvillean, but lacking the 20th-century immediacy of “Airbag.” As for the music, it’s just as lovely as I remember, but the band takes it at a slightly slower pace than was general in its mid-’90s live renditions. This makes the song more deliberate and delicate, but at the same time saps it of energy. The production also lacks some of the high-end sheen of the canonic OK Computer tracks. My guess is that for this belated release, the band’s longtime engineer Nigel Godrich chose to leave things pretty much as they were when the recording was abandoned.

You’d have a tough time arguing that any of these three songs should have taken the place of “Lucky”—or any other tune, for that matter—in the final album running order. “I Promise,” “Man of War,” and “Lift” serve instead as valuable missing links between OK Computer and Radiohead’s previous album, The Bends, test runs for a possible stadium-rock future that the band, probably wisely (for the sake of their own sanity, if nothing else), opted not to pursue. And they do fit splendidly alongside the abundance of superb B-sides and EP tracks that Radiohead produced during the mid-’90s, from “The Trickster” and “Maquiladora” to “Talk Show Host” and “Polyethylene.”

The long-awaited release of these songs adds to a growing sense that major circles are being closed in Radiohead’s career right now.* It’s fairly common practice for them to revisit older material (to pick just one example, “Nude” was written and performed live nearly 10 years before it appeared on 2007’s In Rainbows), but there’s been something different, something more valedictory, about their recent choices. I first noticed this last year, when the band surprised just about everyone by making “True Love Waits”—a song that had first appeared on a Radiohead set list in 1995—the final track of 2016’s A Moon Shaped Pool, in a drastically revised arrangement. Replacing the steady, earnest acoustic-guitar strumming that fans knew from concert performances and the 2001 live EP I Might Be Wrong were ghostly layers of piano gradually superimposed on one another to form an aural palimpsest, not so much parts as memories of parts, recalled only dimly.

Beautiful as this reimagining was, I found the new “True Love Waits” hard to listen to. It was just so sad. This may be an odd thing to say in relation to Radiohead, whose music has always been saturated with gloom; in 25 years, I don’t think they’ve ever put out a song that you could call unreservedly happy. But the emotion being expressed here didn’t seem like the usual free-floating anxiety or depression at the general state of the world. It felt like very personal grief.

Perhaps I’m overinterpreting, but I couldn’t hear this music without thinking about what had preceded its appearance by several months: the news that Thom Yorke and Rachel Owen, his partner for 23 years, wife for 12 of those years, and mother of his two children, had decided to separate. “True Love Waits” was written early on in their relationship; it ends with the words “Just don’t leave/Don’t leave.” That this, of all songs, was picked to close A Moon Shaped Pool just had to be more than coincidence.

Now, of course, the choice of that song can’t help but take on further dimensions of loss. For Owen—a printmaker, photographer, and lecturer in medieval Italian literature at Oxford—died on December 18, 2016, after a long battle with cancer, a little more than a year after her separation from Yorke. She was only 48 years old.

In public, the members of Radiohead have barely discussed A Moon Shaped Pool or the circumstances surrounding its creation. Given their private nature even at the best of times, it would be strange to expect anything else from them. “I don’t want to talk about it anymore, if that’s all right,” guitarist Ed O’Brien told Rolling Stone recently. “I feel like the dust hasn’t settled.” Maybe when Yorke’s children Noah and Agnes are older (they’re now both in their teens), we’ll hear a little more about this period in the band’s history. Or maybe not. For now, all we can say with certainty is that OKNOTOK—with its three treasures from the vaults, all going back to the same golden era that birthed “True Love Waits”—is dedicated to the memory of Rachel Owen.

* Other cases in point: their triumphant return to the Glastonbury Festival 20 years after a career-defining appearance there in 1997, and their choice of Tel Aviv as the 26th and final scheduled stop on their 2017 tour. To anyone familiar with Radiohead’s back story, the controversy over the latter engagement seems a tad silly; this article in the New York Post does a fine job of explaining the band’s fondness for Israel, which has nothing to do with politics. Suffice it to say that without the early efforts of EMI Israel’s Uzi Preuss (whom I interviewed for my book on Radiohead, Exit Music), and the early interest of Tel Aviv DJ Yoav Kutner and his radio listeners, Radiohead might never have been in a position to make OK Computer.