People who died

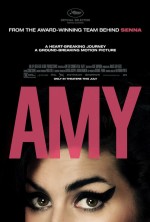

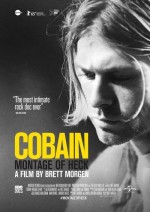

Last week, within a single 24-hour period, I watched Montage of Heck, the new Kurt Cobain documentary directed by Brett Morgen, and Amy, the new Amy Winehouse documentary directed by Asif Kapadia. I guess life was a little too bright and cheery for me that day. But seriously, folks…

Last week, within a single 24-hour period, I watched Montage of Heck, the new Kurt Cobain documentary directed by Brett Morgen, and Amy, the new Amy Winehouse documentary directed by Asif Kapadia. I guess life was a little too bright and cheery for me that day. But seriously, folks…

The coincidence of these two films coming out within weeks of each other only draws further attention to the many parallels in their respective subjects’ lives—parallels that go beyond the grisly truth of their joint membership in the “27 Club.” Both Cobain and Winehouse were the product of broken homes, and both had tortured relationships with their parents as a result. Both suffered youthful bouts of depression, from which further emotional complications sprang. Both chose romantic partners who were no good for them; Winehouse’s passionate dalliance with Blake Fielder quickly turned nightmarish, and the Montage sequences of Cobain at home with Courtney Love do not indicate that theirs was in any way a grown-up relationship. Both fell prey to addiction.

On the positive side, both were intelligent, super-talented, charismatic, and, in their own ways, highly attractive. Watching the expertly assembled footage in Montage of Heck, I was struck anew by the piercing electric blue glint in Cobain’s eyes. And Amy’s awe-inspiring performance clips from the early 2000s made me suspect that if I had met Winehouse in her pre-beehive days, my heart would have melted away. (A lady who’s fond of major-ninth chords can have such effects on me.)

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of both these films is the self-awareness Kurt and Amy display, at least up to a point. Cobain was consciously engaged in creating his own personal legend from early on. So much so, in fact, that one witness to many of the events detailed in Montage, Buzz Osborne of the Melvins, claims that most of the history recounted by Kurt in the film was fabricated. Winehouse understood herself well enough to know that she couldn’t handle fame; she said as much in an interview long before global celebrity came calling.

Cobain both wanted success and didn’t want it, with equal ardor. His natural ambivalence gradually became an unwinnable inner war, lending further allure to the notions of the suicide and the young death that were core components of his psychic makeup. Once Kurt becomes an adult, the shots in which he could be called happy or content are few and far between. Most are home-video clips of him playing with his young daughter Frances. I’d like to think we’re seeing the joy of fatherhood here, but the drugs he was on may have had plenty to do with his mood too. Just look at any clip of him playing with Nirvana: Those cool blue eyes are already fixed on the great beyond.

Cobain both wanted success and didn’t want it, with equal ardor. His natural ambivalence gradually became an unwinnable inner war, lending further allure to the notions of the suicide and the young death that were core components of his psychic makeup. Once Kurt becomes an adult, the shots in which he could be called happy or content are few and far between. Most are home-video clips of him playing with his young daughter Frances. I’d like to think we’re seeing the joy of fatherhood here, but the drugs he was on may have had plenty to do with his mood too. Just look at any clip of him playing with Nirvana: Those cool blue eyes are already fixed on the great beyond.

Winehouse didn’t manifest such an obvious fascination with nihilism and self-destruction, although the revelation of her teenage bulimia does open up a darker side to her character. In any case, it becomes apparent, both to us and to her, that by around 2006 she has ended up somewhere she never wanted to be. The problem is that she doesn’t know how to get out, or does know but can’t muster the inner strength to do so. Sadly, the external support that could have helped her muster that strength is sorely lacking. So for the next five years, she tries alternate escape routes. We all know how that ended.

The music these tragic figures made in life remains, of course, much of it marvelous. So does the bittersweet temptation of wondering what might have been. Maybe Cobain and Winehouse would have become even bigger stars and even more influential if they’d survived. But that may not have been possible. From the evidence gathered by Morgen and Kapadia, there’s good reason to believe that they would just have imploded in some other way, or turned their backs on the music business.

From a purely technical standpoint, Montage of Heck is brilliant; Morgen’s biggest brainstorm—to pair new expressionist animation with audio from Cobain’s archives—pays off big-time, making us feel as if we’re entering Kurt’s imagination. Although not as innovative, Amy is similarly well done. As you might expect, there are powerful moments in both movies. Nirvana’s searing MTV Unplugged performance of “All Apologies” becomes the soundtrack for home-movie footage of Cobain the toddler, mugging for the camera as he eats saltines, a touching reminiscence of innocence lost. Then there’s the scene when Winehouse, watching the 2008 Grammy Awards ceremony from London, sees her idol Tony Bennett announce her win for Record of the Year, and we observe the eyes of a starstruck fan widening between the layers of black mascara. (Later, Winehouse and Bennett record a duet at Abbey Road, and she clearly feels so uncomfortable, so unworthy of being in the same room with him, that it’s hard to bear. Bennett, to his everlasting credit, responds with great kindness, gently pulling her through. If only more people in her life had been able to treat her this way.)

These are just isolated moments, though. In general, my reaction to both films was more muted than I thought it would be. Neither spends enough time explaining how and why Cobain and Winehouse got into music in the first place, missing out on a key point of connection with the audience, who presumably are watching these movies because they care about music. And the onscreen action doesn’t make the deaths of Kurt and Amy any more comprehensible than they were before. It does make those deaths seem more inevitable—they’re the whole reason for these films’ existence, after all—but that kind of inevitability isn’t exactly soul-stirring.

Then again, I may just have been all cried out after seeing the Brian Wilson biopic Love and Mercy, compared to which Amy and Montage of Heck feel far less emotionally satisfying. Why? Maybe it comes down to the difference between a docudrama, which can take liberties with the facts, and a documentary, which is bound to them. Or maybe it’s because, in the end, the story of a survivor is more moving than the retold tales of those who didn’t make it.