Juneteenth in Charleston

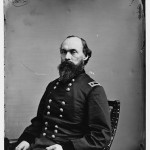

Gordon Granger, who told the slaves of Texas they were free. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

One hundred and fifty years ago today, on June 19, 1865, the news about emancipation in America finally reached Texas, the last Confederate holdout. Union Major General Gordon Granger read these words after his army had secured the port of Galveston: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.”

As we’ve seen over the past couple of days, people are still upset about this development a full century and a half later, and not just in Texas but throughout the former Confederacy. At least one young man in South Carolina was so upset that he felt the need to shoot and kill nine people, including an elected official, in a black church—and not just any church, mind you, but Denmark Vesey’s church (look him up)—while mouthing time-worn KKK-style tropes. The choice of location and date may have been pure coincidence; I don’t know how aware Dylann Storm Roof is of U.S. history. But to those who are aware of it, he was in effect condemning Vesey and his 1822 slave revolt co-conspirators to death a second time, 193 years to the day after that revolt was planned to occur. How symbolic. How constructive.

Others aren’t quite as upset as Roof, luckily. Let’s just call them mildly troubled. Their unease comes out when discussion turns to, for example, the continued flying of the Confederate flag on the grounds of South Carolina’s capitol. This is labeled a “sensitive issue.” In some cases, people are sensitive because they’re aware that their forebears fought and, in many cases, died for the right to keep others enslaved. Such sensitivity is understandable. No one wants to be remembered for defending inhumanity. So why continue to celebrate a horrible mistake?

Because not everyone sees it as a mistake. That’s understandable too, up to a point. Just imagine you were the owner of a big, beautiful plantation in the country, but you didn’t have to do any actual planting. All the grunt work was taken care of by a team of laborers, and you didn’t have to give any of them health insurance or vacation days or pay any of them a dime if you didn’t want to. However you treated them was entirely up to you, and they couldn’t do anything about it because you owned them all. Admit it, that doesn’t sound too bad. Now imagine all that has been taken away from you. By the government. Who then changed the rules to ensure that you can never get your property back. You’d probably think that was utterly unfair. But what can you do? Not a lot, just enough to give yourself some self-respect. You celebrate the life you used to have, praising it with noble words like “tradition” and “heritage,” and you honor the valor of sacrificing oneself for it—never mind that the whole system was built on abominable crimes. And then you call it a “sensitive issue.”

Losers can be very sensitive. Losers who’ve been chewing over a loss that goes back generations can be even more so. And when, aided by the lenient laws of their society, they find themselves in possession of guns and ammo, they can give their sensitivity free and full expression. Perhaps they think that expressing it in such a dramatic way will turn them from losers into winners. They’re wrong.