Dreaming it up with Orson Welles

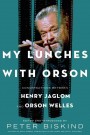

I was lucky enough to spend a few days in the Bahamas recently—a welcome respite from the seemingly never-ending New York winter—and I brought a book along that I thought would be perfect for the trip: My Lunches with Orson, edited by Peter Biskind. The book is essentially a transcription of a series of conversations between Orson Welles and fellow director Henry Jaglom that took place during the final three years of Welles’ life (1983 to 1985) over lunch at his favorite Hollywood restaurant, Ma Maison. Jaglom taped these conversations, apparently at Welles’ suggestion, though the latter’s many opinionated, provocative, and decidedly un-PC remarks indicate he wasn’t all that concerned about being recorded.

I was lucky enough to spend a few days in the Bahamas recently—a welcome respite from the seemingly never-ending New York winter—and I brought a book along that I thought would be perfect for the trip: My Lunches with Orson, edited by Peter Biskind. The book is essentially a transcription of a series of conversations between Orson Welles and fellow director Henry Jaglom that took place during the final three years of Welles’ life (1983 to 1985) over lunch at his favorite Hollywood restaurant, Ma Maison. Jaglom taped these conversations, apparently at Welles’ suggestion, though the latter’s many opinionated, provocative, and decidedly un-PC remarks indicate he wasn’t all that concerned about being recorded.

Reading My Lunches with Orson was even more of a treat than I expected. If you’re at all interested in the history of the movies, the craft of filmmaking, or classic Hollywood gossip, you’ll love it. Instead of subjecting it to a lengthy review, I’ll just present one of my favorite passages. This actually comes from Biskind’s introduction, which delves into the shared history of Welles and Jaglom, who first met when Jaglom was making his debut feature, 1971’s A Safe Place, and hired Welles to star in it (along with Jack Nicholson and Tuesday Weld). During that shoot, the young first-time director was having difficulty getting his more seasoned crew to do what he wanted. He complained about it to Welles, who advised him to tell the crew that they were shooting a dream sequence. The advice worked; as soon as Jaglom mentioned those two words, everyone on the set went from crabby to enthusiastic. But why did it work? When Jaglom pressed for an answer, Welles responded as follows:

“You have to understand, these are people who work hard for a living. They have tough lives. Structured lives. They work all day, then they have dinner, put their kids to bed, go to sleep, and get back to the set at five o’clock the next morning. Everything else in life except for dreams has rules. The only place they’re truly free is when they fall asleep and dream. If you tell them it’s a dream sequence, they will be freed of those rules to be creative, imaginative, and give you all kinds of stuff that they’ve got inside of them.”

My guess is that Jaglom didn’t have his tape recorder running when those particular words were uttered, so it’s hard to vouch for their accuracy. But their wisdom is clear. People who are creative at heart can so easily become uncreative when the work they love turns routine. Someone has to tell them—often repeatedly—that it’s okay to do what they most want to do, that they’re not being self-indulgent, that they need to stop listening to their own inner critics and just try a bunch of stuff. In order to be at their best, they must consciously allow themselves to become unconscious.

Did I mention that I love Orson Welles?