Dream for sale. Contact Randy and Harry.

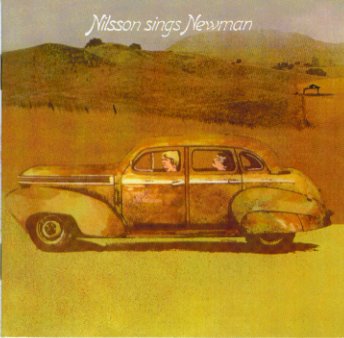

Viewing John Scheinfeld’s excellent documentary Who Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talkin’ About Him?) the other night pulled me back to my favorite Nilsson song, and led me to ponder why I like it so much. The song is his version of Randy Newman’s “Love Story,” from the 1970 album Nilsson Sings Newman. On the surface, it’s about as simple as can be: one piano (played by the composer), one voice, two verses, two choruses, a bridge, and a brief coda. But it packs a lot worth thinking about into three minutes and thirty-nine seconds.

Viewing John Scheinfeld’s excellent documentary Who Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talkin’ About Him?) the other night pulled me back to my favorite Nilsson song, and led me to ponder why I like it so much. The song is his version of Randy Newman’s “Love Story,” from the 1970 album Nilsson Sings Newman. On the surface, it’s about as simple as can be: one piano (played by the composer), one voice, two verses, two choruses, a bridge, and a brief coda. But it packs a lot worth thinking about into three minutes and thirty-nine seconds.

The person singing the song is a salesman. He’s selling the American Dream to a young female prospective buyer. His sales pitch is funny, mainly because a lot of what he’s selling doesn’t sound that grand. But one senses that he’s only partly aware of the humor underlying his proposition. And that makes it all the more seductive.

Item number one on our salesman’s agenda is marriage, and everything that goes along with it. There’s got to be a kid—a boy, naturally—and it’s important that he be “straight” (centuries of prejudice embodied in a single line). Then maybe one day he’ll be president, “if things loosen up.” The man will commute into the city, the woman will raise the children. There will be a few small pleasures amid the general fatigue, like dancing and watching late-night TV. As our salesman projects further and further into the future, the gratitude pours forth from his voice, gratitude he already feels for all that’s to come, gratitude that he wants you to feel too.

And then the master stroke, the logical culmination of our love story: the children, now grown, will send their aging parents off to a “little home in Florida.” The piano’s pace slows, and Nilsson’s voice lingers tenderly over the final couplet. “We’ll play checkers all day/Till we pass away.” The end.

Newman, of course, is pop music’s leading ironist, and typically for him, there are multiple layers of meaning here, several of them droll. You could say, with some justification, that the point of “Love Story” is to poke fun at 20th-century suburban striving; the vision of life Nilsson and Newman are presenting to us, though beautifully packaged, is hollow at its core. Except that it may not be. For many of us, it seems very much like the real life we live. We work, we have fun when we can, we raise a family maybe, we get old if we’re lucky. And let’s face it, most of us aren’t going to be president unless things loosen up. A lot. Does that mean we shouldn’t appreciate what we have? Or that we should consider our lives devoid of purpose?

The original version of “Love Story,” which opened Newman’s 1968 debut album Randy Newman Creates Something New Under the Sun, is outstanding. Delivered in the warm Southern drawl that would soon become Newman’s trademark but was at the time still in its early development stages, the words—and the character behind them—are completely believable. And yet the mock-heroic sweep of strings at the end, pretty as it is, seems to weight the song more toward the humorous end of the scale.

No strings are present or necessary in Nilsson’s version. The pristine sweetness in his voice is enough to add another dimension to the salesman’s pitch. His honeyed tone makes the whole thing so tempting, not just the wedding but everything that follows: the years of commuting, the nights in front of the tube, the countless games of checkers in that little Florida home. It’s a wonderful life indeed. And that makes the end a deeply moving moment. When the singing stops, so does the song—a simple death with no great ceremony. The elegance of the music is lovely, but nearly as endearing is the salesman’s ardent belief in the value of what he’s selling. We get the joke, but we chuckle with tears in our eyes.

In Scheinfeld’s documentary, Newman calls working with Nilsson “a pretty big honor for me, a milestone in my life.” As “Love Story” shows, it was a milestone in more ways than one. Together, these two inimitable American creators came up with a funny little pop tune that’s also a serious piece of high art.