A Blurry look back (Part 1): The intro

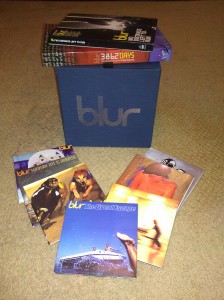

My previous post referred to an upcoming Blur album, the band’s first in 12 years and first with its original lineup in 16 years. That album, The Magic Whip, is now available to all and has been widely lauded by the press, including me in The New York Observer. Listening to it repeatedly put me in a retrospective mood. I found myself re-reading 3862 Days, Stuart Maconie’s official Blur biography, published in 1999. Next I re-watched No Distance Left to Run, the documentary about Blur’s reunion and U.K. tour in 2009. Then I did a rather self-indulgent thing and bought Blur 21, the boxed set issued in 2012 to celebrate the 21st anniversary of the band’s first major-label release. How self-indulgent? 21 discs (18 CDs and 3 DVDs), that’s how.

In an attempt to justify this crazy purchase, I decided to make my way through the discs in order and record my thoughts. As an addendum, I figured I’d revisit the one interview I conducted with all four members of Blur, following their soundcheck at New York’s Roseland Ballroom (RIP) on February 10, 1996. Some snippets from that interview appeared in a piece I wrote for the July ’96 issue of Musician, but most of it has never been seen before.

That last bit will make up the final part of this series. First, Blur 21. Having now listened to the entire thing, what strikes me most is how different the band sounds at the start from the way it sounds at the end. Of course, most bands that last a while change over time (except maybe AC/DC). The creative evolution of Radiohead has been particularly fascinating to me, and I’m drawn for similar reasons to the Kinks or U2 or Wild Beasts, to name just three. Even so, the distance Blur traveled in its initial 12 years on EMI, from 1991 to 2003, is astonishing. Looked at purely in terms of the number of styles they explored—and the number of times they changed their artistic direction—they rival the all-time great shapeshifters of modern pop: the Beatles, Dylan, Bowie, Prince, Madonna, perhaps a handful more.

Do they also match those artists in terms of quality? Not exactly. Of the 213 songs in the core catalog of Beatles recordings, there are a bunch of throwaways, but I can’t think of a single one that I wouldn’t be amenable to hearing again. Of the 282 songs on the first 18 discs of Blur 21, there are enough tracks that I could have done very well without hearing the first time to fill at least one disc, maybe a disc and a half. But that still leaves 16½ discs of material ranging from decent to brilliant. Not an awful batting average, by any means.

You could argue that unlike the Beatles or Dylan or the others mentioned earlier, Blur wasn’t innovative, and that’s hard to dispute. Britpop, the one subgenre you could justifiably claim that the band invented, was so clearly indebted to the work of other British bands in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s that it seems wrong to call it an invention. And yet, even through all the chameleonic donning and divesting of stylistic accoutrements, Blur’s music established and maintained an essential personality that’s quickly identifiable and unlike anyone else’s. You can hear it in the thorny guitar asides of Graham Coxon, which pull at the seams of songs that seem painstakingly pieced together and lead them somewhere unexpected. You can feel it in the crisp, supple drumming of Dave Rowntree, which generally takes a supportive role but can step forward and pummel listeners’ ears when required. It’s there in the bass work of Alex James, a vastly underrated player who combines the melodic flair of the Attractions’ Bruce Thomas with the groove-centric virtuosity of Duran Duran’s John Taylor. And it’s there most of all in the melodies, lyrics, and voice of the band’s leader, Damon Albarn.

As easy as it can be to appreciate Albarn’s talent and skill as an artist, it’s tough to actually like him. Many people find his vocal style grating, especially as it was in the mockney pomp of Blur’s high Britpop phase. Being a lifelong Anglophile, I’m not so bothered by this aspect of the band, but even I will admit that for someone who famously sang, “There must be more to life than stereotypes,” Albarn certainly sounded like one himself in the band’s early days. And therein lies one of the many pleasures of listening to Blur 21 in sequence: hearing how his singing subtly morphs over time from a twee caricature of an artsy, borderline-irritating English person into the voice of a believable three-dimensional human capable of real depth and surprising pathos (a development that continues on The Magic Whip, I’m happy to say).

Okay, enough prologue. On to the discs themselves, which I’ll examine in Part 2.